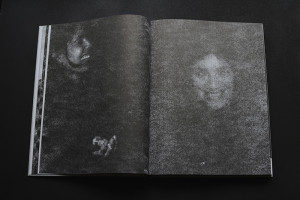

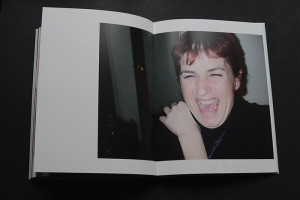

Laughing Inverts

photographs 2006-2010

Artist book, first limited edition 24, 2011

Artist book, 16,4 x 24 cm, 200 pages, 82 color- and 44 b/w images, texts in german and english by Diedrich Diedrichsen and others, Kehrer publisher Heidelberg-Berlin, 2015

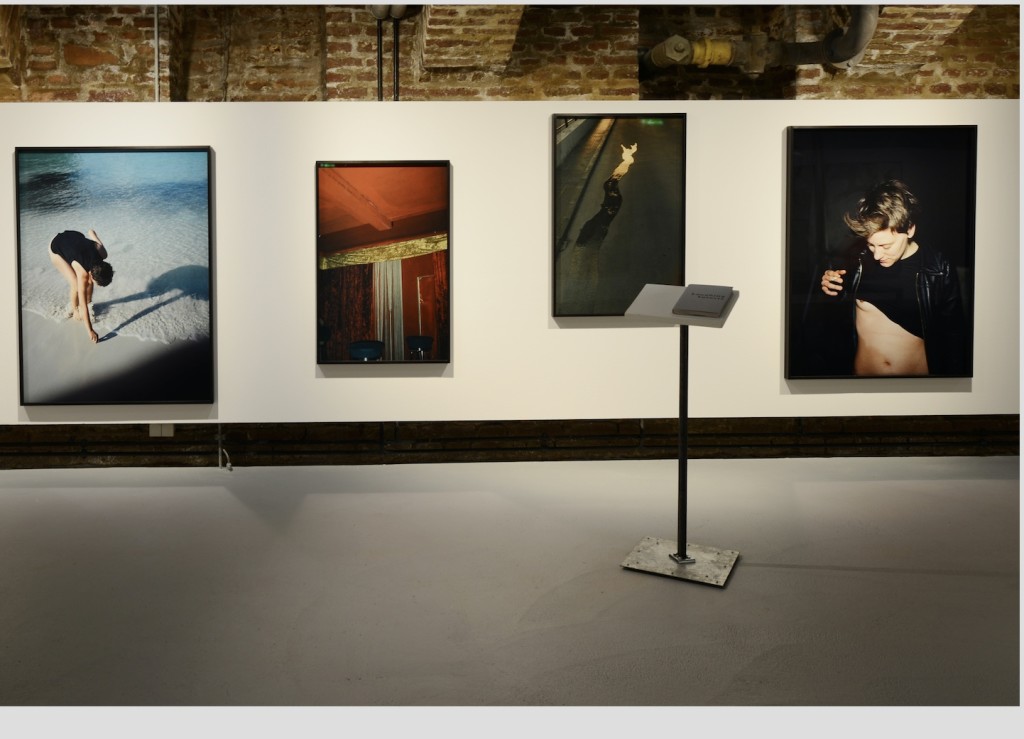

3 analogue c-prints 100 x 120 cm, 2 analogue c-prints 70 x100 cm, 1 analogue c-print 60 x 80 cm, 1 digital c-print 60 x 80 cm, all framed behind museum glas

Please click into the image to enlarge

Laughing Inverts, I DREAMT WE WERE ALIVE, KUNST HAUS, Vienna, 2017

Dust in Strange Light, LLLLLL Gallery, Vienna, 2019

Laughing Inverts, Kehrer Publisher, 2015

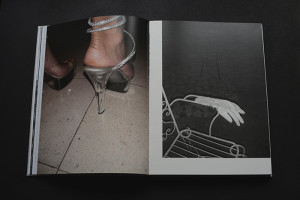

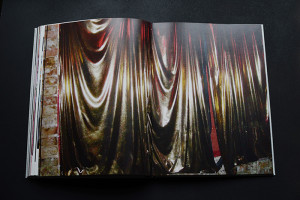

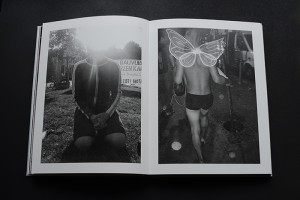

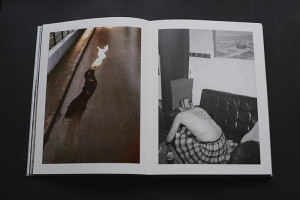

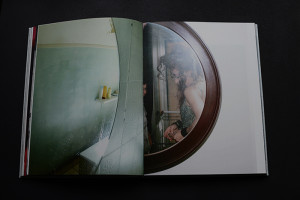

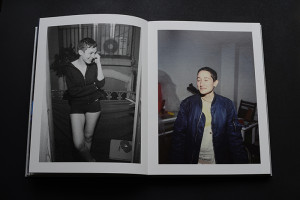

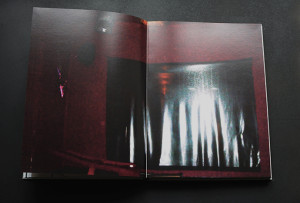

The phenomenon of laughter, like this artist’s book, is characterized by variety. The diversity of photographic approaches manifested in the dialog between these images reveals different facets of identity, relationships, and social movements. Momentary scenes arise in the mix of imagery, forming idiosyncratic orders. Found signs and traces are articulated in movement, masquerade, and glamour. Visual shifts, reversals, and reinterpretations invert societal norms and conventions. Browsing through these pages, a flow of images emerges that follows its own inner rhythm, united by the expressiveness of laughter as communication, gesture, grimace, or threat.

Jump Cuts, Laughing Inverts, 2015/ text by Diedrich Diedrichsen

The last time I read the term inverts was in Proust, or more specifically in the translation of research by Eva Rechel-Mertens. It is one of those antiquated words for homosexuality that now seems to make it possible to describe non-heterosexual orientations differently than through narrow classifications like homo or bisexual. It actually seems appropriate for contemporary projections, because it bespeaks twists, turns, and folds that are more reminiscent of a Möbius strip than a two-part society in which we either belong to one part or the other. Indeed, Proust uses the term in the multifaceted sense.

On one hand, the inverts have anything but a solid foundation of a simply antagonistic, anti-normal sexual orientation beneath them. Unlike a significant part of contemporary queer theory, which emphasizes overcoming the gender binary in favor of an open continuum in a liberating sense, for Proust it was precisely the polarity of man and woman that ensured endless depths. Because within every woman could be a man or another woman, within every man a woman (or another man), and the same thing would be repeated on the next level in a complex branched system of increasingly more confusing bifurcation. The inversions continue spiraling downward and undermine every clear vision of orientation, but not without using the two sides again and again.

On the other hand, Proust sets the real heteronormative world surrounding him in fiction as a great lesbian conspiracy. Because in the novel, Proust’s real male lovers become women (in order to avoid outing himself), who, when they resign themselves to the heterosexual pressure of reality, begin relationships with women who then become inverted – i.e. lesbians – in the fictional perspective. This results in an unreality in which normal appears as though it were always inverted, where as the world of the inverted is merely another twist and turn of those people who were already twisted or ready to turn anyway.

In Lena Rosa Händle’s book Laughing Inverts the subjects have long since plunged into this abyss and have let the Mobius strip of inversion show them the tangled way – albeit not necessarily tragic, bitter and heroic, like in so many stories, and also not melancholic. Instead, as the title suggests, laughing. This laughter is not coming from the distance of a safe, possibly ironic position; it is the laughter of people who are in the thick of it – and yet often somewhere else.

t first glance, the book follows a certain tradition of sub and counterculture photography that is based on testimony and mainly communicates that another life, which few can imagine to be real, was or is possible – which is why it requires the testimonial medium of photography.

One need only think of the often diary-like depictions of Larry Clarke, Peter Hujar, or Nan Goldin’s own circles of friends living on the edge, also with shifted focal points Wolfgang Tillmans’ early work. But what distinguishes the described practices, both historically and in their artistic character, is that the artists mentioned above generally try to cohere the story and the sequence of images. The dialectic of the subcultural in its classical period, specifically liberation at the expense of compartmentalization to attain exclusivity, was incredibly effective.

Lena Rosa Händle’s approach is almost the opposite of this. Although we can assume that the scenes from the exciting, intense, excessive life that we see here are not taking place far away from each other socioeconomically and that they include people who not only share commonalities of life content, culture, and politics, but actually know each other or could have met, each photograph seems like a new world to us. Changing the frame of reference is the main strategy of the whole story, more than that of each photograph. Outside/inside, natural/artificial light, group/individual, interaction with the camera/absorption, transparent readability/opacity – all of these contrasts and their potential modulations are thoroughly savored in the sequence of the individual photographs.

The result is a quality of photography that is only just evolving, mainly in the sequential storytelling element of the book, which literally presents photography’s political-subcultural side in a very different light than what was common in earlier (self) representations – the artist appears in at least one photograph. What we see is a precarious, threatened, more crisis-laden environment, a world in which there are no more guaranteed safe spaces. But at the same time, there is no exclusion and formation of a subcultural elite, which was associated with earlier movements and scenes. The outness and openness that characterizes these images leads to laughter with which the subjects confront the situation you end up in today if you want to lead a life that someone sang so dreamily about more than a half a century ago: I don’t know where I am going, I don’t know who I am going to be.

The fact that someone manages, wants to and has to manage, to make such a decision without the starry-eyed self-elevation, the eternal and latent colonial adventurism, that someone has and had to establish themself in an everyday life that has the advantage of being attainable, the disadvantage of actually being threatened by the inhospitality of cities (which cannot be avoided) and their prices – that is the situation that is acknowledged here with a laugh.